One day soon, a menu may judge you.

You’ll walk up to a kiosk in a quick service restaurant and a tiny camera will scan your features, registering your height, age, gender, and mood. Instantly, it will adjust its display, selecting meal options picked just for you.

Once you’ve ordered and moved on, the person behind you will step into the menu’s gaze, and the process will start again.

This is the idea behind new software from Raydiant, a San Francisco-based software company that plans to roll out its AI-driven kiosks by the end of this year. The intention, according to CEO Bobby Marhamat is to create a personalized experience for customers, while helping restaurants boost sales.

“Our company initially started as a digital signage company. Customers [businesses] wanted to use analytics to create better experiences within their locations,” says Marhamat. Raydiant started developing the AI technology in 2013.

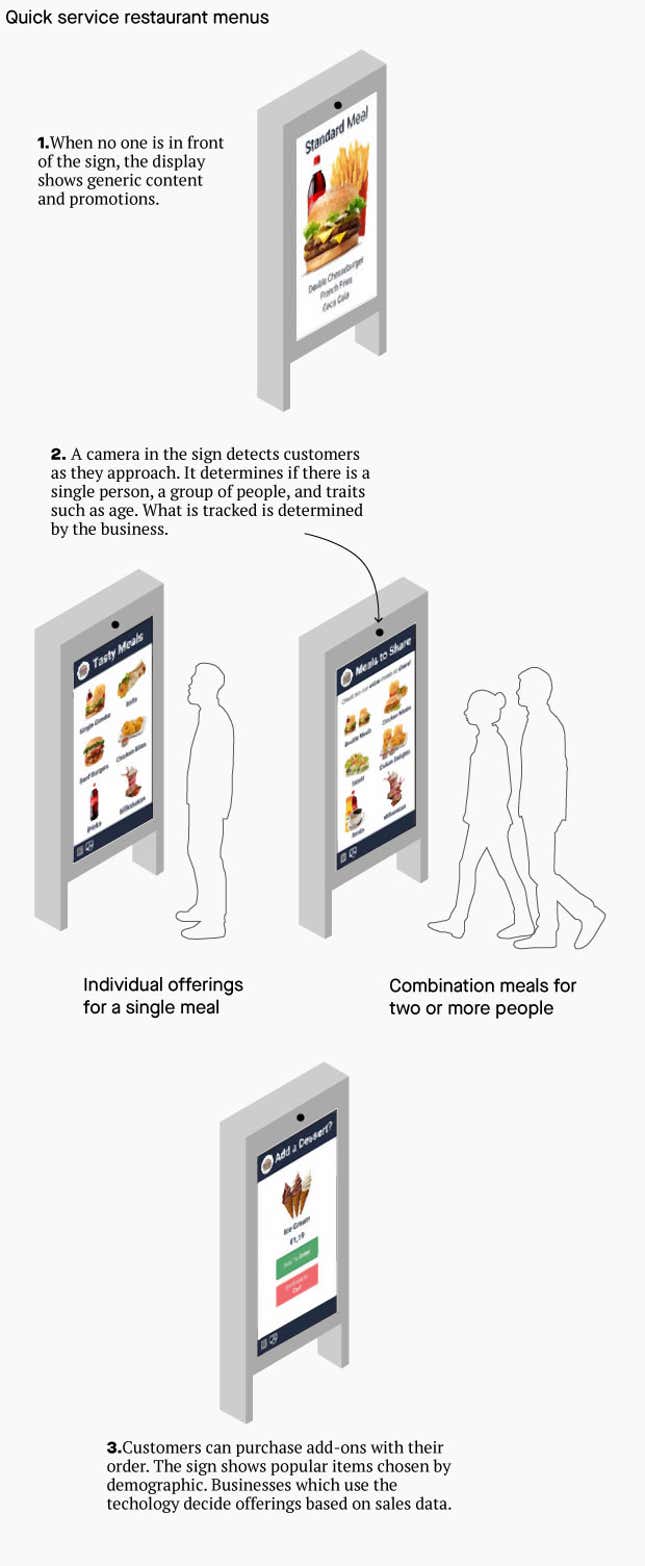

Here’s a look at how Raydiant’s kiosk works:

Raydiant’s technology, though not implemented yet with AI experiences, is used by more than 4,500 organizations around the world, from stores to gyms to casinos.

Businesses themselves determine the criteria for age, gender, and other characteristics. “Typically larger brands make their own definition. The smaller brands follow the bigger brands,” explains Marhamat.

Raydiant established rules around what kinds of categories the AI can sort. Race and body size are off limits. Gender, Marhamat says, is way down the list of sorting options that brands prefer to use. “Most brands are not looking at gender right now. They’re looking at age group, time of day…different inputs.” Age groups are classified based on facial features like wrinkles. Mood is subjective and based on inputs like weather. “What was identified is if it’s raining and someone doesn’t like the rain, they’re walking in discontent, the mood on their faces is being picked up as discontent.”

Why Raydiant says the tech is not creepy

When Bon Appetit wrote about the new software, the magazine called it “creepy” for self-evident reasons. AI systems can be biased, playing into and reinforcing age and gender-based stereotypes. As technology advances, how personal data is used, whether anonymous or not, is a concern with groups working to advocate for data privacy.

Marhamat, not surprisingly, disputes such characterizations. Customers do not need to worry about data privacy and face scans, because his company doesn’t save individualized data or sell it to third parties, he says. People can also opt out of having their features recorded by not using the AI-enabled kiosks.

But the technology raises some gnarly ethical questions. Food ads are powerful drivers of consumer behavior. Does Raydiant have some responsibility to guide its restaurant clients toward ethical marketing decisions? Wouldn’t it be immoral to, say, effectively hide menu images of salads or fruit from young customers, the very people who are prone to fall victim to fast-food advertising?

Every brand that adopts Raydiant’s kiosks sets up its own system, he says. “We don’t control it, the brands control it. It’s more like we’re giving them the ability.” Marhamat says Raydiant provides businesses with privacy documentation to help them adhere to legal guidelines. On the backend, Raydiant claims the technology is designed with privacy by default, which means only anonymous data is processed and collected. Businesses can also activate a blurring functionality on top of the analysis.

“It’s the early days of making people feel comfortable using this technology to better their experiences,” says Marhamat.

Raydiant’s technology is made for quick-service restaurants and is unlikely to ever move into the full-service restaurant space, says Marhamat. Still, Cameron Fraser, restaurant industry veteran and service and beverage director at Flame and Smith, in Prince Edward County, Ontario, says he finds the premise depressing, no matter where the product is being deployed. “It’s more tyranny of the algorithm,” he says.

Algorithmic marketing is crossing over into physical space

Raydiant’s tool is also part of a wider trend in retail, Marhamat says. Brands will soon be routinely using face-scanning software to typecast customers and cross-promote products that may fit their niche. “If you go to the yoga pants section, is there an ability to put an ad for yogurt that’s in a different section of the store?” he says.

Categorizing customers by demographic or type means the majority’s preference determines what ad you get, even if you don’t fit the norm. Whether or not we’re ready for the implications of these changes, online siloing may soon be happening offline.

Fraser compares the smart menu kiosk to digital music services that push hit singles, making an artist’s full body of work, or albums, less visible. Your approach to food—as with music, books, or films—should be about exploration and expansion, he says, not based on algorithmic recommendations.

“The joy is in the discovery and the novelty,” says Fraser. “Otherwise, what are you going to do? Eat the same ham and cheese sandwich every day?”